This website uses the name Japanese military “comfort women” instead of “military comfort women”(従軍慰安婦) or “comfort women” (慰安婦). The reasons are as follows.

Wartime Designations

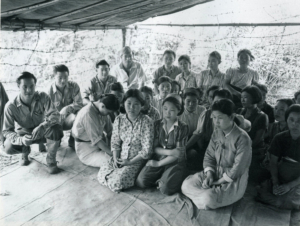

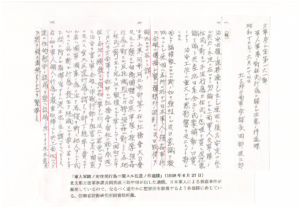

To begin with, the Japanese military “comfort women” system began with the establishment of comfort stations for Japanese army generals in 1932 in Shanghai, China, which was invaded by the Japanese army. The comfort stations were expanded throughout mainland China and even to other Asia-Pacific countries, and until the defeat of Japan, women from Asian countries, including Japanese, were made “comfort women”. At the time, the Japanese military referred to these sexual facilities as “comfort stations”(慰安所), “military comfort stations”(軍慰安所), “comfort facilities”(慰安施設) and “canteens”(酒保). It referred to the women as “comfort women”(慰安婦),“military comfort station attendants”(軍慰安所酌婦),“special women”(特種婦女), “special comfort women”(特殊慰安婦), “military comfort station employees”(軍慰安所従業婦) and more discriminately, “peas”(ピー),“comfort natives”(慰安土人) etc. (according to official documents).

Popularization of the term “military comfort women”

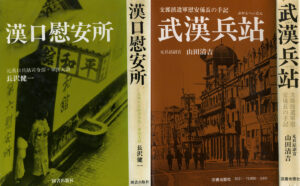

For a long time after the war, this issue was largely forgotten in Japanese society, although it was occasionally the subject of novels and movies. However, the term “military comfort women” (従軍慰安婦)became popular after journalist Kakō Senda published his book “Military Comfort Women – 80,000 Accusations from Voiceless Women”(『従軍慰安婦―“声なき女”八万人の告発』) (Futabasha) in 1973. According to Senda, he coined the term “military comfort women,” and the book, including its sequel, became a long seller, selling 700,000 copies (according to an interview in 2000). The term is still used today, which demonstrates the book’s powerful influence.

In fact, during this period, Suzuko Shirota (pseudonym), a Japanese “comfort woman”, published “Maria’s Hymn”(『マリアの賛歌』) in 1971, in which she confessed her past, and in 1975, Bae Bong-ki, a Korean “comfort woman” in Okinawa, came to light. However, at that time in Japan, there were no social movements, women’s movements, or academic research aimed at resolving this issue.

Survivor Testimonies and the Clarification of the Reality of the “Comfort Women” system

A major shift occurred in Asia. In 1990, a women’s movement was launched in democratized South Korea, and in 1991, Kim Gak-soon came out for the first time and demanded compensation from the Japanese government, saying that she had been made a “comfort woman”. This was followed by a series of simultaneous testimonies from victims in other Asian countries. This was the #MeToo movement of the 1990s. These testimonies revealed the concrete and diverse nature of the damage caused by sexual violence on the battlefield. In addition, military archives and testimonies from former Japanese soldiers have been unearthed, and academic research has helped to clarify the reality of the situation.

The shift to the term Japanese military “comfort women”

In the early 1990s, the name “military comfort women” was proposed for review at the Asia Solidarity Conference (「アジア連帯会議」)(formed by support groups from various countries), which sought to resolve this issue.

The reasons for this are as follows: (1) The name “comfort women” was given by the Japanese military, and the term “comfort” derived only from a male (Japanese military generals) perspective, and for women it was nothing more than “sexual slavery,” as they had no freedom to leave the comfort station, live outside, go out of business, or refuse to work. The term “Japanese military” was added to clarify where the responsibility lies, because the term “military” does not make clear to which country this military belonged and implies that the women followed voluntarily.

As the actual situation in each country became clearer, the term “wartime sexual violence” came to be used to distinguish the strong aspect of violent abduction, confinement and continuous rape by the Japanese military experienced by women in the occupied territories, such as China and the Philippines, from the Japanese military’s “comfort women” system, which was systematized and institutionalized through fraud and cajolery, as was the case of women in colonial territories. Women were forced into sexual slavery by the Japanese military in both cases.

The International Spread of Japanese Military Sexual Slavery

“Ianfu” is translated into English as “Comfort Women,” but when this issue became an international problem in January 1992, it was translated into English as “Sex Slaves” in the foreign media, and in February of the same year, the term was used for the first time at the United Nations. The term “ianjyo” (“comfort stations”) was also translated into English. UN spokesman Gay McDougall called it an “inexcusable distortion” and said that rape centers were the essence of the term.

Thus, since the mid-1990s, the term Japanese military “comfort women” (/system) or “Japanese military sex slaves” (/system) has been used. An example of the latter use is The Women’s International War Crimes Tribunal to Try Japanese Military Sexual Slavery (日本軍性奴隷制を裁く女性国際戦犯法廷), held in Tokyo in 2000. Thus, it can be seen that survivors’ testimonies and clarification of the actual situation prompted the change in the term.

As mentioned above, this website refers to the Japanese military as “comfort women,” with the term “comfort women” added in the sense of criticism of the Japanese military, in order to clarify where the responsibility lies.

Political Intervention by the Japanese Government

As a result of the above, the terms Japanese military “comfort women” and “Japanese military sex slaves” have become widely used in academic research (the term “military comfort women” continues to be used by many scholars). In addition, until 2021, the term “military comfort women” was commonly used in history textbooks. The Japanese government has intervened politically in these matters.

First, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs has posted on its website that the expression “sexual slavery” is “contrary to the facts,” and has repeatedly expressed this assertion to the international community. For example, on February 16, 2016, Shinsuke Sugiyama, Deputy Vice Minister for Foreign Affairs, stated at the United Nations Headquarters in Geneva that “expressions such as ‘sex slavery’ are contrary to the facts.” As mentioned above, the term “Japanese military sex slaves” is a well-established international and academic term, and to call it “contrary to the facts” is a serious issue.

Furthermore, on April 27th, 2021, the Government of Japan stated, “The Government of Japan considers it appropriate to simply use the term ‘comfort women’ instead of ‘military comfort women’ or ‘so-called military comfort women’ because the use of the term ‘military comfort women’ may lead to misunderstandings. As a result, The Government of Japan has been using the term ‘comfort women’ in recent years.”

As a fundamental issue, it is dangerous and disrespectful of historical facts for the cabinet to decide on the interpretation of history and terminology at the convenience of the current administration. It is also highly problematic that the cabinet decided to ignore the results of academic research and deny that the Japanese military “comfort women” system was forced upon women against their will, and that the term “military” should be removed with the intention of erasing the existence and responsibility of the Japanese military (as mentioned above, in recent years, the term Japanese military “comfort women” or “Japanese military sex slaves” has become more widely used, but the term “military comfort women” is also used in academic research, and we consider it problematic that this term is denied due to political intervention).

Intervention in Textbook Writing

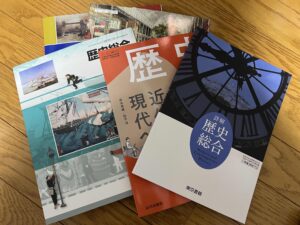

Based on the above cabinet decision, there has been intervention in textbook writing.

In 2014, the “Textbook Authorization Standards” (教科書検定基準)were revised and the following statement was added.

“In cases where there is a unified government view expressed by a cabinet decision or other means, or precedents of the Supreme Court, the text shall be written based on such rulings.”

This is a provision that stipulates the intervention of state power in textbook writing by forcing the inclusion of government views in textbooks, and it has been pointed out as problematic.

Based on the “Textbook Authorization Standards”, pressure was exerted on textbook companies in 2021. In response, textbook companies submitted applications to correct the descriptions of textbooks that had already been published, such as deleting the word “military” in “military comfort women,” and the descriptions were changed.

Furthermore, there have been requests to revise terms such as military “comfort women” in the textbooks that will be used from the 2023 academic year and these descriptions have also been revised.

The above is political intervention in textbook writing, and cannot be tolerated. It is a denial of academic freedom and freedom of speech and publication, as well as a distortion of textbook writing based on empirical research for political purposes, and cannot be overlooked.

The Japanese government should embrace the historical background and its own responsibility and use the name Japanese military “comfort women”.

<References>

Senda, N. (1973) Military Comfort Women – “Voiceless Women” 80,000 People’s Accusations (『従軍慰安婦―“声なき女”八万人の告発』). Futabasha.

Yoshimi, Y. (1993) Military Comfort Women (『従軍慰安婦』). Iwanami Shinsho.

McDougall, G. (2000) How to Judge Wartime Sexual Violence: The Complete Translation of the UN McDougall Report (『戦時・性暴力をどう裁くか―国連マクドゥーガル報告全訳』). Kaiwasha, 1998, enlarged and updated edition.

Kurahashi, K. (2018) Historical Revisionism and Subcultures: Media Culture of Conservative Discourse in the 1990s (『歴史修正主義とサブカルチャー―90年代保守言説のメディア文化』). Seikyusha.