Some people deny the veracity of the victims’ testimonies by saying that they “have undergone dramatic changes”, for example that there was no mention that they were forced to work by the army or other governmental organization (THE FACTS, “Washington Post”, June 14th, 2007). But can we really deny a fact simply because they didn’t mention it in their initial testimony? And does testimony itself become unreliable if its content changes? Let’s discuss a bit about how to approach the testimonies of these victims.

1 Memory and Trauma

Generally speaking, it is true that some of the female victims’ testimony is vague with respect to when something happened, where it happened, and who was involved. Some who were in China and East Timor are even vague about their date of birth. And some who know that they were taken to China don’t remember specifically where.

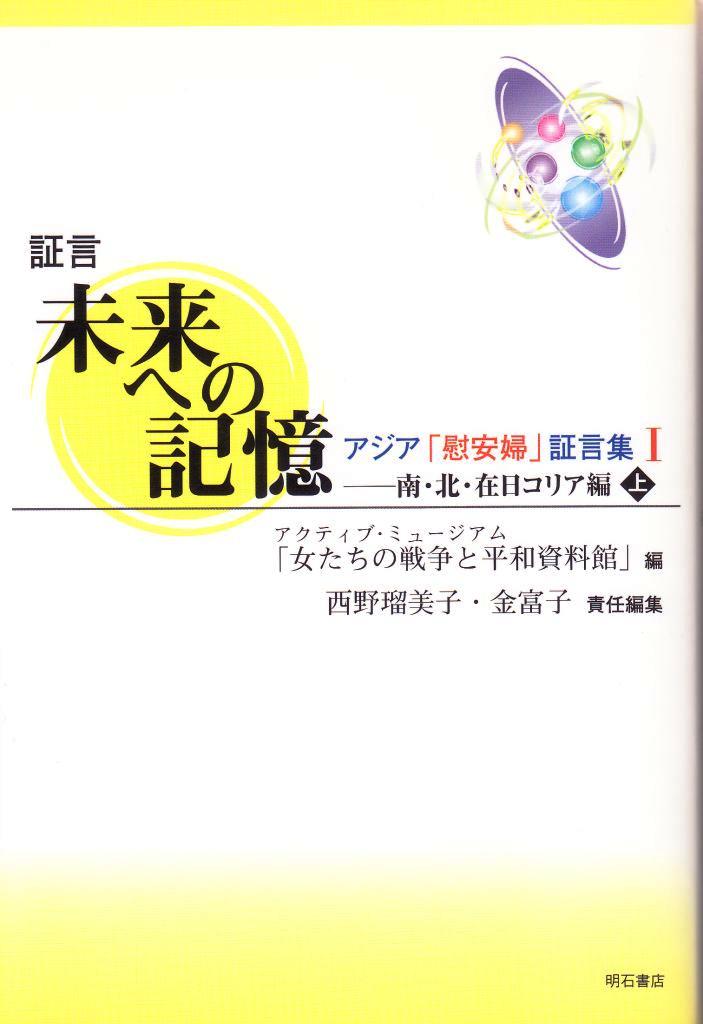

For example, in the case of Mun Pil Gi, who was taken to a comfort station by train, she remembers that she went to Manchuria by way of Sinuiju, but she doesn’t remember things like the name of the place where the comfort station she was taken to was located, nor the name of the military unit using the comfort station. (Shogen mirai e no kioku ajia ianfu shogenshu – minami kita zainichi korea hen jo [Testimony, Memory for the Future, Testimony Collection Ⅰ by Asian “Comfort Women”―North, South Koreans and Koreans in Japan] Edited by the Women’s Active Museum on War and Peace, Akashishoten, 2006, pp.165-177)

But in fact the women talk in amazing detail about some things, for example they give precise descriptions of comfort stations, being visited by huge numbers of Japanese soldiers, that soldiers stood sentry over the stations, or the manner in which they were taken off to the stations. When you hear a person speak in detail about “what happened”, you can understand she has experienced pain and anguish that time has been unable to erase. Even if she suffers from a partial loss of memory or doesn’t remember a proper name, her entire testimony can’t be ignored as unreliable.

Issues related to memory are not limited to the question of forgetfulness after a long period of time. For example in colonized Korea, women in particular lacked education, and in 1932 alone, 91.2% of Korean women had no experience of the futsu gako (“normal schools”) (Kim Pu-ja, Shokumichi Chosen no kyoiku to jenda [Education and Gender in Colonial Korea] Publ. Seorishobo, 2005). Being unable to receive an adequate school education, many of these illiterate women couldn’t depend on their memory for the written word, but instead relied on things they heard. We have to appreciate this situation when we listen to the victims’ testimonies.

Fragmentation and loss of memory also shows that the women suffered serious damage. Psychiatrist Kuwayama Norihiko explains that fragmentation of memory is “a phenomenon in which a person has vivid memories that are vivid in and of themselves, but there is a lack of clarity about how the memories are related to one another, or where they fit in the sequence of time.” And he says that the essence of trauma is “a broken state in which a person is caused psychological damage by an extremely painful event from which they feel they are unable to recover, crushing their hope to live and destroying important personal relationships.” (Kuwayama Norihiko, Chugokujin moto ianfu no shinteki gaisho to PTSD [Trauma and PTSD Suffered by Former Chinese Comfort Women], Kikan Senso Sekinin Kenkyu [The Report on Japan’s War Responsibility] Vol.19, 1998)

According to Judith L. Herman, this is peculiar to people with traumatic memories (Judith L Herman, Trauma and Recovery: The Aftermath of Violence from Domestic Abuse to Political Terror [Previous ed.: 1992] ed.). 1996). A victim is still suffering severe trauma when she opens her mouth for the first time. Giving inconsistent and fragmentary testimony is a symptom of PTSD (Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder). However, in the process of establishing “Safety” (a “Stage of Recovery”, together with “Remembrance and Mourning” and “Reconnection”), in which someone listens sincerely to her story, her frozen memory is gradually melted.

According to Herman, the women in the 1990s breaking their silence and beginning to talk about what they suffered were in a Stage of Recovery. A new environment, in which someone began to listen to their experience without harming them, opened the door to recovery from damage. Making personal attacks (that their stories are fabrications, or that they are lying for money) are acts of further violence against these victims.

2 How Should We Deal with Kim Hak-sun’s Testimony?

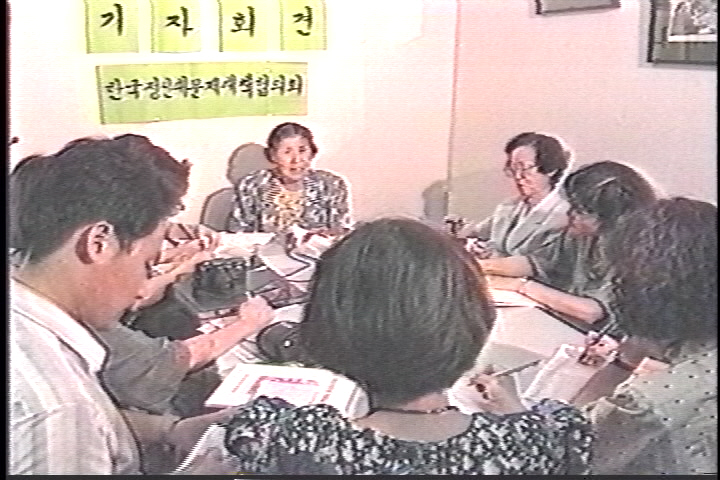

Kim Hak Sun’s August 14, 1991 Press Conference at the

Korean Council for the Women Drafted for Military Sexual Slavery by Japan

Some people often deny the veracity of Kim Hak-sun’s testimony, saying that there is a difference in nuance between what was written in the complaint when she first sued and things she said later, or that she concealed the fact that she had been a kisaeng, a type of Korean female entertainer.

For example, a table entitled “Discrepancies in Kim Hak-sun’s Testimony” is included in Hata Ikuhiko’s Ianfu to senjo no sei ([“Comfort Women and Sex in War”] Publ: Shinchosha, 1999). It lists the below as the circumstances under which she says she was forced to be come a comfort woman, and yet a careful reading shows us that she gave consistent testimony:

A: “Being suspected to be a spy by Japanese officers at a restaurant in Beijing, she was separated from her adoptive father and taken to a comfort station by truck…”

B: “The same as A.”

C: “Japanese soldiers threatened her adoptive father and took her to a comfort station…”

C may be technically different in that she mentioned that Japanese soldiers “threatened her adoptive father.” However, since it can be interpreted that her adoptive father was threatened when he was “suspected to be a spy,” it doesn’t mean the testimony itself conflicts. What is more, since it she hasn’t wavered from the fact that she was separated from her adoptive father and that Japanese soldiers took her to the comfort station by truck, it can’t be said that her testimony has changed. A person may be reminded of something as their memory becomes more vivid upon repetition of the testimony. Just because she didn’t mention it in testimony at the time doesn’t mean we can reject everything she has said.

Moreover, it doesn’t matter whether someone forced to become a “comfort woman” was a Korean female entertainer or not. What matters is that she was forcefully taken to a comfort station by truck. If her adoptive father “sold” her to soldiers before she realized it, it means that Japanese military was involved in human trafficking in female minors. If so, it is a matter of grave concern since it was a crime under the Penal Code of the time. (Article 224, Kidnapping of Minors) stipulates that a person who kidnaps a minor by force or enticement shall be punished by imprisonment, and Article 225 of the same Code (Kidnapping for Profit) stipulates that a person who kidnaps another by force or enticement for the purpose of profit, indecency, marriage or threat to the life or body shall be punished by imprisonment.

3 Both the Kono Statement and Successive Prime Ministers Have Acknowledged the Use of Coercion by ‘Testimony.’

The Kono Statement acknowledged that coercion had been used in the recruitment and retention of “comfort women”. The reason Kono Yohei released the Statement was upon listening to the stories of sixteen female victims. He said, “They offered explanation after explanation on the situation known only to those who had experienced such tremendous hardships,” and that considering the situation, it was a sufficiently reliable story from various angles (Asian Women’s Fund, “Oral History―Asian Women’s Fund” in March, 2007).

Since the time Prime Minister Hashimoto Ryutaro took office, successive Prime Ministers including Abe’s first Cabinet have all adhered to the Kono Statement. The reason the government has given for acknowledging the use of coercion is that “There was no mention in the documents investigated by the government that directly pointed to so-called forcible recruitment (of comfort women) by the military or government authorities. We acknowledged the use of a certain level of coercion from an overall examination of the issue.” In other words, the government has historically recognized the truth of the women’s testimony.

4 The Victims Shouldn’t Be Obliged to Find Out Who Was Responsible.

In any case it is a useless endeavor to look to the women’s testimony in order to ascertain who managed and supervised the comfort stations, who issued the orders to establish them, and by whose orders the victims were taken there. That is because these women were directly deceived by police officers, ward mayors, and business people. They have no way of knowing who masterminded the system or gave the orders to recruit.

To point to the women’s testimony and say that we can’t see the people responsible doesn’t mean they don’t exist. It is not the victims, but the Japanese Government that is responsible for finding out the truth of what actually happened, by means of the victims’ testimony.