We hear the claim that “there are no historical documents proving the Japanese military forced women into prostitution”. (“The Facts” June 14, 2007) Is this really true?

We hear the claim that “there are no historical documents proving the Japanese military forced women into prostitution”. (“The Facts” June 14, 2007) Is this really true?

Setting aside the issue of how we define force or coercion, which has been discussed in other places on this website (for example in Q&A numbers 1-1 and 1-2), in this section we will focus purely on the issue of the value of using written documents as data.

First of all, official documents are not the sole resources used in verifying facts. Not only official documents, but also private documents and oral testimony can be used as legitimate data. Whatever the form the historical materials take, they must be carefully examined. Who produced them and when? For whom and for what purpose did they come into being? In the case of official documents, it is common for the Government (or the politicians or bureaucrats in charge in each case) to use language that sounds plausible but is in fact rhetoric used to justify their actions by white-washing inconvenient truths.

There are numerous testimonies of the former comfort women themselves, as well as those of veterans attesting to how these women were recruited and how they were treated at comfort stations.

If you were to limit your resources to official documents, you’d never find a piece of paper that says “make them comfort women any way you can, even if you have to force them.” One reason for this is that the authorities don’t issue documents that are likely to get them in trouble later. Orders and instructions tended to be worded vaguely (this tendency is still prevalent in bureaucracy today) and specifics and crucial points were often communicated verbally. We can cite the very nature of official documents as a cause in the persistent dearth of this kind of evidence existing as testament to the sordid nature of the comfort women system.

Yohei Kono who put forth the Kono Statement when he was Cabinet Chief explained it in the following way. “If coercion is defined as being recruited against your will, clearly numerous cases full under coercion. Can we really imagine that officials would give orders to recruit women ‘against their will’, and reports would say things like, ‘we coerced the women into coming with us’? Think of Japan at that time. Unlike today, the military dominated politics, the economy, and society. The military was strong enough that it could forces its own decisions on the National Diet if the Diet tried to resist. Given the situation, how could any woman refuse in the face of such massive power?” (Asahi Shimbun Newspaper, March 31, 1997) They are well-considered remarks, showing both common sense and understanding. Such common sense seems to have lost its place in the Japan of today.

Yohei Kono who put forth the Kono Statement when he was Cabinet Chief explained it in the following way. “If coercion is defined as being recruited against your will, clearly numerous cases full under coercion. Can we really imagine that officials would give orders to recruit women ‘against their will’, and reports would say things like, ‘we coerced the women into coming with us’? Think of Japan at that time. Unlike today, the military dominated politics, the economy, and society. The military was strong enough that it could forces its own decisions on the National Diet if the Diet tried to resist. Given the situation, how could any woman refuse in the face of such massive power?” (Asahi Shimbun Newspaper, March 31, 1997) They are well-considered remarks, showing both common sense and understanding. Such common sense seems to have lost its place in the Japan of today.

The other issue is the large-scale purge of military and government documents carried out upon Japan’s WWII defeat. In the case of the Army, all units were commanded to incinerate their documents on August 14, 1945 and they commenced to do so immediately. The Home Ministry, in charge of the police force, ordered local police branches to do the same.

Seiryo Okuno, who served as government official of the Home Ministry at the time of the defeat, and is one of those who claims the comfort women to have been involved in “commercial transactions”, in fact stated the following in a 1960 round-table discussion:

“After the decision to incinerate documents was made, it was communicated through each organization in its own manner: the Army and Navy top-down, while on a civilian level the order went out to prefectural governors and municipalities. They couldn’t do it openly so the Chief of General Affairs called for a meeting and finalized details by coordinating with the Army and Navy, ultimately giving the order to the Governor-Generals. We were aware that the US could land in Japan on any day after August 15, and it was a bad idea to let any documentation be seen by them, so we decided to communicate verbally and to minimize putting things into writing. Kobayashi, Bunbei Hara, Yoshio Miwa and I took in charge of communication with different sections around the country. (Jichidaigakkō shiryō henshū-shitsu “Yamazaki naimu daijin jidai o kataru zadan-kai” [“Round-Table Talk about the Era of Home Minister Yamazaki”, The Office of Historiography of the Local Autonomy College], 1960)

So we see that Okuno has admitted in a round-table discussion to having paid visits to local authorities to get them to incinerate documents, and even that their reason for doing so verbally was because they thought it would be a “bad idea” to let such instructions be seen by the U.S.

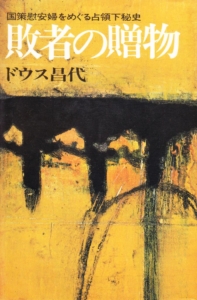

There is more evidence in things we learn from the person in charge of establishing the RAA in Tokyo, a section chief of the Metropolitan Police Department Economic Police. This section chief has said that he repeatedly emphasized to his junior officers from the Public Security Division, “Due to the nature of this work, which is not part of your official police duties, all the instructions must be communicated verbally”. “Do not leave behind written documents”. He also said that “things related to prostitution were mostly instructed verbally”. (Haisha no okurimono [Gifts of the vanquished], Masayo Duus).

There is more evidence in things we learn from the person in charge of establishing the RAA in Tokyo, a section chief of the Metropolitan Police Department Economic Police. This section chief has said that he repeatedly emphasized to his junior officers from the Public Security Division, “Due to the nature of this work, which is not part of your official police duties, all the instructions must be communicated verbally”. “Do not leave behind written documents”. He also said that “things related to prostitution were mostly instructed verbally”. (Haisha no okurimono [Gifts of the vanquished], Masayo Duus).

Among bureaucratic organisations – of which the military is one – it has commonly been the practice to use oral instructions instead of producing written documents when nobody wants to be held accountable. We are left with those who are themselves accountable for destroying the evidence defiantly claiming that their coercion cannot be proven.

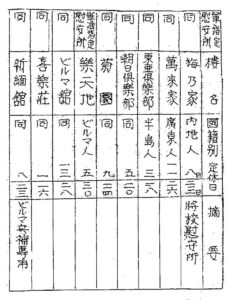

Due to the systemic destruction of documents, the Japanese Military documents which we have access to today are meager in number, and fall into the category of either having been 1. confiscated on the battlefield by the Allied Forces, or 2. secretly kept by some Japanese officers. And despite the importance of official documents, it must be noted that they can prove only a partial view of what happened. Not only that, government and military officials have tended to hide problems that are inconvenient or which they don’t want to face.

Another reason we lack official documents is because some have not been made public. In Japan, freedom of information legislature has now been passed, so we have some sense of what documents exist in the present (meaning documents used by authorities presently), but there are many things unclear about the state of disclosure of historical documents (although the situation is considerably improved from the way it used to be). At the initial government investigation, the National Police Agency didn’t come up with any documents regarding the comfort women, but later in December 1996 they discovered quite important documents at the National Police Academy. This must be only the tip of the iceberg in unidentified archive materials.

It has become a principal among democratic nations that official documents ought to be declassified in 30 years, or after a certain period of time. By the same principle, the Japanese government should all release official documents regarding pre-war, wartime and post-war proceedings.