A massive number of the victims of the Japanese military’s comfort women system couldn’t go to school or left school before graduating, and were consequently illiterate. Was this a special case during the colonial period in Korea?

First of all, as opposed to on the “Mainland” (Japan), a compulsory education system wasn’t implemented in Korea until August 1945. Hence many children couldn’t enter elementary school. (Note: elementary schools for Koreans were called futsu gakko [normal schools] until the 1937 school year, jinjo shogakko [ordinary elementary schools] from the 1938 school year, and kokumin gakkou [National schools] from the 1941 school year.

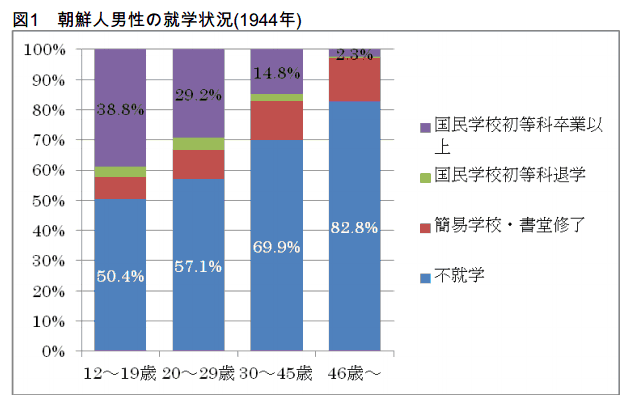

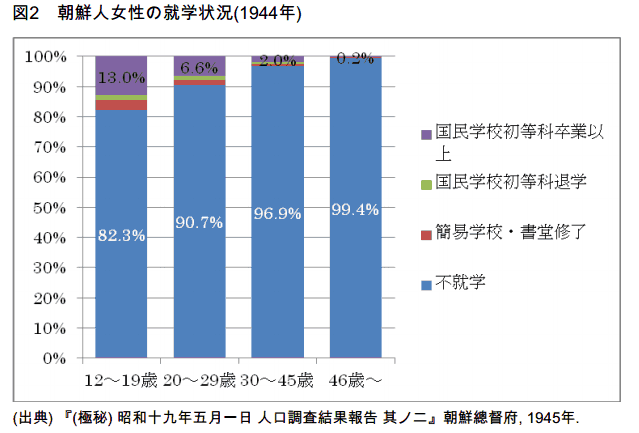

Below are the results of a survey conducted in 1944, during the final stage of the war (Figures 1 and 2, Japanese only). We have to recognize that a huge portion of Korean society had no experience with school attendance, as shown by the blue portion of the charts below. Here we see the figure divided by age, and in particular, there was a great difference between men and women. 57.1% of men and 90.7% of women between the ages of 20 and 29 had no experience with education. In other words, nine out of every ten women would have never gone to school.

By contrast, because of a policy among the Japanese in Korea to establish elementary schools in their place of residence, almost all of these so-called “mainlanders” could go to school. Only 0.8% of Japanese men and 1.2% of Japanese women in Korea between the ages of 20 and 29 had no experience with school attendance. In other words, there was an overwhelming difference depending on your ethnicity.

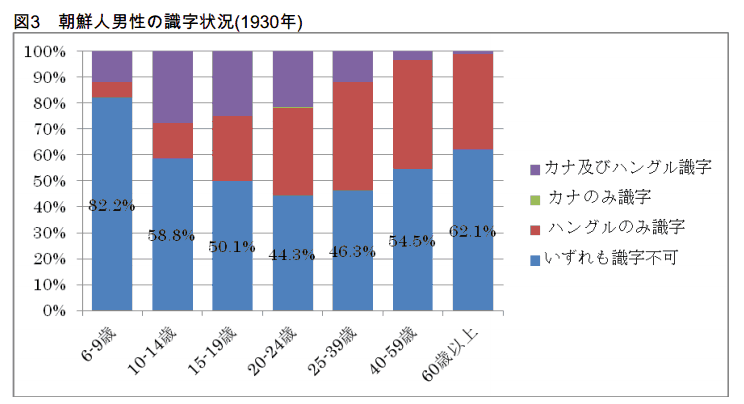

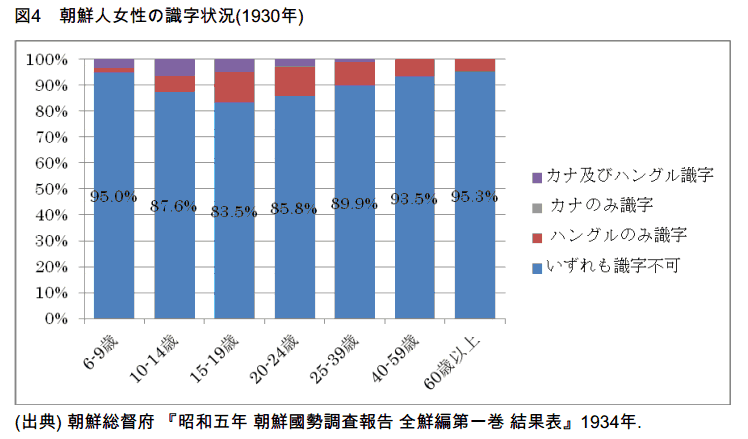

Still the literacy rate was in fact higher than the school attendance rate, as reading and writing was in fact also taught at home in some cases, or outside of the educational system. Below are the results of the 1930 National Census (Figures 3 and 4, Japanese only) Yet as once might expect, we see that the percentage of women unable to read and write Japanese kana (syllabic Japanese script) and hangul (Korean script) was overwhelmingly higher than that of men, with the numbers at 44.3% for men and 85.8% for women between the ages of 20 and 24.

It is incorrect to attribute these results to insufficient education in Korea. During the Joseon Dynasty (1392-1897), there was a high degree of literacy because of private schools like the seodang (similar to terakoya in Japan), widely established in rural areas, with study focused on classical Chinese. Hunminjeongeum (Korean script), which was invented in the 15th century, was also variously used, for example in teaching classical Chinese education, or as a communication tool for women of the upper class. Starting from the end of the 19th century, the orthography of public and private documents was gradually converted from classical Chinese to the “national language,” a mix of Korean script and Chinese characters, and significant changes were also made to the educational system. All kinds of private schools increased particularly as Japan began encroaching on the nation, and in the year of 1909 alone more than 2,000 were established.

Then befell the “annexation”. Private schools were closed down or suppressed. Even well-equipped educational facilities were labeled “private academic schools” and put in the unstable position of having to obtain approval every year. By contrast, so-called futsu (normal) public elementary schools played the leading role in the school system. These aimed at nurturing “national character” and teaching the “national language” (Japanese). But these schools weren’t established so easily. It wasn’t until the middle of the 1930s that there was one school was for every myeon (a unit denoting a town or village). And they weren’t “established for the benefit of Korean children” by the Government-General of Korea. In fact, the Government-General of Korea used the donation of land and construction funds by influential local figures to approve the creation of schools that included the integration of the “private academic schools” mentioned above and were forced to adopt a Japanese curriculum.

Before the adoption of compulsory education, primary education could only be obtained through the payment of tuition. For that reason, impoverished families found it difficult to send their children to school. For instance, according to the results of a survey in one region, 63% of landowner families and 6% of tenant farmer families sent their children to school. (South Jeolla Province, Kosaku kanko chosa sho [A Survey of Tenancy Customs], 1923) Therefore there was also a class difference (wealth disparity) in school attendance.

In examining the roots of the gender disparity in school attendance, we have to look at the system and at society. In the case of the co-educational “normal” elementary schools, there was usually a difference in admissions numbers between men and women. This would be a systematic factor. And impoverished families with many children, being unable to send all of them, usually favored sending their sons to school over their daughters. This is a social factor. Such a combination of systematic and social factors caused the school attendance disparity between men and women.

We see how in colonial Korea a combination of ethnicity, class and gender came to effect whether you able to go to school and / or become literate.

When we approach the issue of the low literacy rate in Korea, we also have to remember how the multiplicity of languages and methods of writing complicate the situation. During the colonial period, although the Japanese language maintained dominance, there was a lopsided mix of tongues: Japanese and Korean, and scripts: kana (Japanese syllabic system), Chinese characters and hangul (Korean script). After Japan’s defeat, North Korea and South Korea both abolished the Japanese language and launched a Korean script literacy movement called the “extermination of illiteracy”, and North Korea declared it finally exterminated in 1949 (Chosen kyoiku shi 3 [History of Education in Korea 3], Publ. Shakai Kagaku Shuppansha, 1990). The percentage of South Koreans unable to read decreased sharply from 77.8% in 1945 to 41.3% in 1948, down to and 13.9% in 1954. (Bunkyo geppo [Monthly Educational Report], No.49, November 1959)

Seen this way, the circumstances of colonialism in Korea had not a positive but negative impact on school attendance and literacy.

References:

Kim Pu-ja, Shokuminchi chosen no kyoiku to jenda (Education and Gender in Colonial Korea) (Seorishobo, 2005)

Itagaki Ryuta, Literacy Survey in Colonial Korea, Journal of Asian and African Studies, No.58, 1999)

http://repository.tufs.ac.jp/handle/10108/21863