“Comfort Women” Weren’t “Licensed Prostitutes”.

People who deny that “comfort women” suffered personal harm insist on the following:

“The ianfu who were embedded with the Japanese army were not, as is commonly reported, ‘sex slaves.’ They were working under a system of licensed prostitution that was commonplace around the world at the time. Many of the women, in fact, earned incomes far in excess of what were paid to field officers and even generals …, and there are many testimonies attesting to the fact that they were treated well.” (‘THE FACTS’, “Washington Post”, June 14th, 2007)

Under the system of licensed prostitution, specific operators and women were licensed to engage in prostitution and were registered with the police. This system was adopted in pre-war Japan. According to the above argument, “comfort women” were “prostitutes” licensed at the time.

However, this argument is wrong. “Comfort women” weren’t “licensed prostitutes”. Many of the victims forced to become “comfort women” were women who had nothing to do with the system of licensed prostitution or prostitution. It is clear that “comfort women” victims were enlisted by the Japanese military or operators ordered by the Japanese military by means of violence, fraud or human trafficking, etc. and forced to become sex slaves under the control of the military at comfort stations. The women forced to become “comfort women” couldn’t retire or act for themselves without the military permission.

What is a System of Licensed Prostitution?

Then, what was the system of licensed prostitution in pre-war Japan? Specific operators and women in specific areas, including the areas which had been red-light districts or post towns since pre-modern times, were licensed to engage in prostitution. For the purpose of preventing the spread of sexually-transmitted diseases, the women were required to have STD examinations. The system of licensed prostitution was justified by the rhetoric that it prevented sexually-transmitted diseases and rape. Under such a system, many poor women committed prostitution in pre-war Japanese society.

When shogi (licensed to commit prostitution under the system of licensed prostitution), geigi (although their main business was singing, dancing and musical performances, often forced to commit prostitution) and shakufu (connived to commit prostitution), etc. started their business, they made contracts with shops for a definite period of time. Prostituted women, whether they also had to perform singing, dancing or musical performances or not, were subject to indentured contracts.Significantly, though, their parents received cash advances for being a contracting party or co-signer. And until the debt was paid off, their daughter had hardly any freedom of retirement. In other words, they were virtually sold by their parents.

In pre-war Japanese society where it was considered a virtue to devote oneself to ones parents or family, prostituted women were forced into such a situation. Moreover, a significant percentage of the money that customers paid for their prostitution was collected by operators as revenue, and the women’s debts were paid off from the remainder which was her share. So it took a long time to pay off the debt, and it often became impossible to pay it off because it constantly increased. Under the system of licensed prostitution in Japan, women were forced into prostitution without personal liberty until they paid off their debts, which was extremely difficult. As a result, many died of diseases including sexually-transmitted diseases or committed suicide.

The Regulations for prostitutes enacted in 1900 stipulated that freedom of retirement was guaranteed even before paying off cash advances. However, a cash advance contract was regarded as a financial loan and the women were obliged to pay it off. So, having no other way to pay off their debts, women were forced into prostitution with almost no freedom of retirement. It was clear that the cash advance was lent with the intent of making the daughters enter prostitution without freedom of retirement. To dismantle the custom of selling daughters into prostitution, these cash advance contracts should have been criminalized. However, the courts made judgments in favor of geisha house operators. Moreover, even at that time, the inhumane system of licensed prostitution as described above was called the “slavery” and should have been abolished based on international standards of the suppression of the traffic in women.

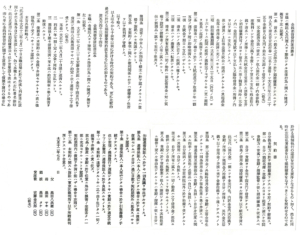

Prostitutes’ contracts

As stated above, it’s not an exaggeration to say that the inhumane system of licensed prostitution was a system of sexual slavery. What matters in thinking about the issue of the “comfort women” is that some women were enlisted as “comfort women” through being taken advantage of in their lives of prostitution without freedom of retirement.

Examples of prostituted women Enlisted as “Comfort Women”

As a matter of fact, there were examples in which women were enlisted by the military or operators to become “comfort women” through being taken advantage via the custom of lending cash advances.. At present, it is known that most of these examples were those of Japanese “comfort women”. In other words, while it is true that “comfort women” weren’t licensed prostitutes, there were nonetheless some who had originally been prostituted and were subsequently enlisted as “comfort women”.

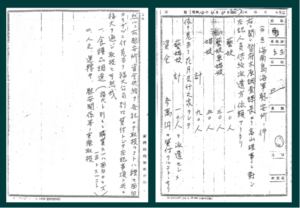

For example, according to material related to the National Police Agency, geisha house operators in Kobe and Osaka, etc. were requested by the Special Intelligence Agency of the Army in Shanghai to enlist women who had been prostituted as “comfort women” to work at comfort stations serving the Shanghai Expeditionary Army in Gunma, Yamagata, Kochi, Wakayama, Ibaraki and Miyagi prefectures, etc. in early 1938. They enlisted women by paying cash advances (Asian Women’s Fund (eds), “Compilation of materials related to the government survey of ‘comfort women’”, Vol.Ⅰ, Ryukeishosha, 1997, p3-112. Also refer to Nagai Kazu, ‘A study of the establishment of army comfort stations and recruitment of comfort women’, “Study of the 20th century”, No.1, 2000).

An extract from materials relating to the National Police Agency about Wakayama prefecture

In addition, according to the personal notes of former medical officers and staff in charge of comfort stations, operators under the system of licensed prostitution were cooperating to establish comfort stations and enlist women. For example, in Nagasawa Kenichi, “Hankou comfort station” (Toshoshuppansha, 1983) and Yoshida Seikichi, “Wuhan Logistics―Personal note by the Chief of Staff on comfort stations for the China Expeditionary Army” (Toshoshuppansha, 1978), it is specified that operators doing business in the red-light districts of Osaka and Kobe were ordered by the military to set up comfort stations in Hankou. Testimony clearly shows that military authorities managed and supervised operators of the comfort stations.

Also, according to testimony from “comfort women” victims, it is clear that prostituted women were enlisted by the military as “comfort women” (As typical examples, see Senda Kako, “Comfort women”, “Comfort women, Keiko” and Shirota Suzuko, “Songs in praise of Maria”, Kanita Publishing Department, 1971). For example, Yamauchi Kaoruko, who was born in 1925, was sold to a geisha house in Tokyo at 300 yen as a cash advance as a child because of poverty and had worked as a geisha under the name “Kikumaru”, heard that the military would erase her debts, so she decided to become a “comfort woman” and went to Truk in March, 1942 (Hirota Kazuko, “Testimony records Comfort women and Military nurses Lamentations of women living in the battlefields”, Shinjinbutsuohraisha, 1975 etc.). Her debt amounted to 4,000 yen and she had no other way to pay it off. Another reason why she enlisted as a “comfort woman” was that she thought “If I die, I will be enshrined at the Yasukuni Shrine for war heroes” and “I would be able to serve the State”.

However, it must be emphasized that the fact women who had been prostituted became “comfort women” doesn’t mean they weren’t sex slaves. As stated above, the women who had been prostituted in pre-war Japan were under unacceptable circumstances of sexual slavery with almost no freedom of retirement. They had no chance of retiring and were looked down on by society. To escape from such circumstances, the fact that the military would erase their debts and the chance to serve the State is likely to have been attractive to them. In actual fact, however, they weren’t enshrined at Yasukuni Shrine even if they did die while in comfort stations. And even if they did come back alive, once their pasts as “comfort women” were revealed, they were looked down on by society and had to lead a life of hardship after the war. In other words, taking advantage of their difficult circumstances, the Japanese military and operators ordered by the military mobilized them as “comfort women”, took advantage of them at their own convenience and then abandoned them.

It is true that the “comfort women” system was different from that of licensed prostitution, but they were connected in terms of both being systems of sexual slavery. Therefore, we must question ignorance and low level consciousness in relation to human rights among those people who say that the comfort women were ‘licensed prostitutes’ and not sex slaves.