Beginning in the Sino-Japanese and Russo-Japanese wars, and in particular during its colonial rule of Korea, Japan suppressed independence movements during times such as the Donghak Peasant Revolution, the Righteous Army Wars, the March First Movement, the Jiandao Massacre, and the guerilla war fought against it by Koreans in Manchuria. Moreover, it violated the human rights of Korean people through things such as the 1923 Kanto Massacre of Koreans, forced labor during WW2, and the “comfort women” system.

However, there is a deep-rooted perception in Japan that the incidents mentioned above occurred under “out-of-the-ordinary” circumstances (war, emergency, etc.) and that the “ordinary” state of the colonies was not war or emergency, but that people lived “peaceful” lives. Certainly there is no question that the colonized peoples had their own daily lives. However, the opinion that peaceful everyday life was a benefit brought about by the modernization of colonial rule is too one-sided. In one instance, the comic book Manga kenkanryu (translated in English as Hating the Korean Wave) emphasizes that Japanese tried hard to “modernize” the Korean society and one of the characters says, “At that time, Japanese and Koreans were friends.”

Those who see colonial rule in this way might think lightly of the kind of violence mentioned above occurring under it, if they think of it as exceptional and out-of-the-ordinary. They might justify it as action necessary in stabilizing the colony and ensuring public safety. In contrast, such a way of thinking sees the daily norm as mutual cooperation and understanding between the rulers and those being ruled. However is it really possible to so simply distinguish what was the “daily norm” from that which was “out-of-the-ordinary” in Korean society under Japanese colonial rule? And can the life the people of the Korean Peninsula lived at that time truly be described as peaceful?

150 Years of the Korean Peninsula Not “At Peace”

First let us take a look at the modern history of the Korean peninsula. Korea has not had peace since the 1860s or the 1870s, as it has been wrought by things like invasions, military interventions, colonial rule and conflict among its own people. The “ordinary” in the lives of the Korean people has also never been immune from these kinds of political tensions.

The things that have caused the Korean peninsula to be “not peaceful” for the last 150 years may be divided into three parts as shown below.

First are the effects brought about by the relationship between Japan and the Korean peninsula. Starting from the Ganghwa island incident and the battles between the Japanese army and the Donghak Peasant Army during the First Sino-Japanese War, and later during the Russo-Japanese War and through the occupation of Korea, the Japanese military and police fought battles against anti-Japanese forces. This means that most people, uninvolved in the anti-Japanese movements, led their daily lives under the control of the military and the police, making the difference between “peacetime” and “wartime” difficult to discern (see below for a more detailed explanation).

Even after the war ended, Japan and the United States continued to be complicit in maintaining military tensions in the Korean Peninsula. Every time there is a crisis, Japan’s public and private sectors call in unison for strengthening of both the Japan-US Security Alliance and the Nationalism of the State, as an emergency response to the “exceptional situation” that is the “Korean emergency”. When a crisis occurred in the peninsula at the beginning of December 2010, the first action the Kan Administration carried out was to cancel the process to obtain free education in Korean Schools in Japan.

The second reason the peninsula has not been “at peace” is brought about by the state of international affairs around the peninsula. The purpose of the Sino-Japanese and Russo-Japanese wars was domination of the Korean peninsula. The battles to control East Asia – including the power grabs of the Western powers against the Japanese military, and China’s attempt to maintain its traditional tributary rule – had begun. The Korean government had promoted a “neutralization” plan to balance the power of Korea and the great powers of the world including Japan, China and Russia. The “order” that the Imperialist nations created reflected their own interests in terms of goods and ignored the will of the Korean people. It was during the course of the Sino-Japanese and Russo-Japanese wars that the Western powers came to agree amongst themselves (giving Korea no voice in the issue) on transferring Korea to Japan’s sphere of influence, making it a colony of Japan.

In particular, the United States has had great influence on the peninsula. The nation let Japan make Korea its protectorate in the 1905 Taft-Katsura agreement. Although President Wilson is known at this time for having been an advocate of internationalism, he was reluctant to recognize the independence of Korea. The U.S. disregarded the hopes of the Koreans and recognized the country as an “incomplete state”, without the power of self-government. After the end of WWII, the Korean peninsula was divided along the 38th parallel and the concept of a multilateral trusteeship was based on the idea of not determining self-governance until the stronger powers were co-managing Korea, and making sure that after independence it would still remain under the influence of the United States. Movements of Korean people demanding total independence have been suppressed under the Cold War between the major powers of the world and the new order of the world as led by the United Nations. The peninsula became fixed as two Koreas after the end of the Korean War and the major powers have continued to make decisions that alternately strain and ease tensions in the peninsula.

The third cause of a lack of peace is the strife brought by civil war. When we talk about civil war in the peninsula, it goes beyond merely the conflict between the Republic of Korea and the Democratic People`s Republic of Korea. There is also a conflict between people in independence movements and the chinilpa (literally: people friendly to Japan) who collaborated with the Imperial Japanese Government during its colonial rule (they came about through factors related to the first and second topics above), and this conflict itself was a factor in the conflict between the North and South. Chinilpa demanded not independence but the maintenance and expansion of Korean rights and interests. The conflict between the chinilpa and people involved in the ethnic movement for independence against the tyranny of colonial rule started during the Righteous Armies Wars, getting severe when the colonial era actually began. Those among the chinilpa who were army and police officers not only ruined the peace of Korean society during colonial rule, but even after the Liberation, with the support of the U.S., they burrowed deep into the heart of the South Korean army and police organizations.

As mentioned above, the 150 years of the peninsula lacking a state of peace has three aspects. In order to stabilize the peninsula and the Japan-Korea relationship, the reconciliation of the two Koreas is not enough. Japan should account for its history of colonial rule, building a peaceful relationship with the North and the South, which means supporting peace and reunification, and finally end the “Korean War”, really an international war that is still embedded in the Korean peninsula.

“War to maintain public order” called Subjugation of the Insurgents, aimed at reorganizing Korea into a colony

Next we will take a look at how difficult it is to distinguish the “ordinary” from that which is “out-of-the-ordinary” under colonial rule in such a “non-peaceful” political climate. As Japan colonized Korea after the Russo-Japanese War, two types of movements started. One was the Patriotic Enlightenment Movement, an urban-centered movement born in the context of the enlightened political power, the Gaehwapa (Enlightenment Party), and aimed at effective cultivation of education and industry. The other was a nationwide anti-Japanese war waged by the Righteous Armies. Japan’s response was to reorganize Korean society, and repeatedly suppress these swelling movements completely through military force in a “war to maintain public order” called Boto tobatsu (Subjugation of the Insurgents). A word commonly used at the time to describe it was yocho, “thorough punishment”, and the suppression was relentless. Scorched-earth tactics were used in clearance of anti-Japanese bases, and villagers were punished even for guilt by association.

For example, in September and October 1909, the Nankan dai tobatsu sakusen (Major Subjugation Operation in Southern Korea) was carried out against the Righteous Armies throughout Jeolla. Its aim was said to be to show off “the dignity of the empire” to Koreans and “promote Japanese business in Korea”, in other words the driving of “development” and Japanese interests. During the process of colonization, both “development” and the “war to maintain public order” were carried out at the same time. Therefore we see it is not so simple to separate “development” (equated with peace and friendship between Japanese and Koreans) from mob suppression (seen as an exceptional “war to maintain public order”), calling the first “ordinary” and the second “out-of-the-ordinary”. And the “war to maintain public order” that was waged was also an opportunity to sustain tensions in Korea under Japan’s rule.

The Jieidan kisoku (Self-Defense Force Regulation) introduced in November 1907 to suppress the Righteous Armies involved placing self-defense forces in villages under command of the Military Police, the police, and military forces, for the purpose of seizing weapons, encouraging allegiance, intelligence reconnaissance, and surveillance patrols. The idea was to smoke out members of the Righteous Armies, and it served to escalate the friction between control and resistance that was a part of people’s everyday lives. In particular, influential people like local government officials, military police assistants and police officers would be criticized by fellow Koreans for being chinilpa. And the Public Security Preservation Law was enforced against the Patriotic Enlightenment movement on July 27, 1907 enabling interior ministers to dissolve associations and the police to prohibit rallies and large events.

The transfer, extension, and penetration into daily life of the “war to maintain public order”

The anti-Japanese Righteous Armies were almost completely suppressed around the time Japan annexed Korea in 1910. But, that doesn’t mean it was possible to make a clear distinction between “the ordinary” and the “out-of-the-ordinary”. Even post-annexation, Japan feared the Korean people as if they were a riotous reserve army and used a policy of policing “with teeth”, using half military forces, on the same scale as when they cracked down on the Righteous Armies; in other words, continuing control by the Military Police.

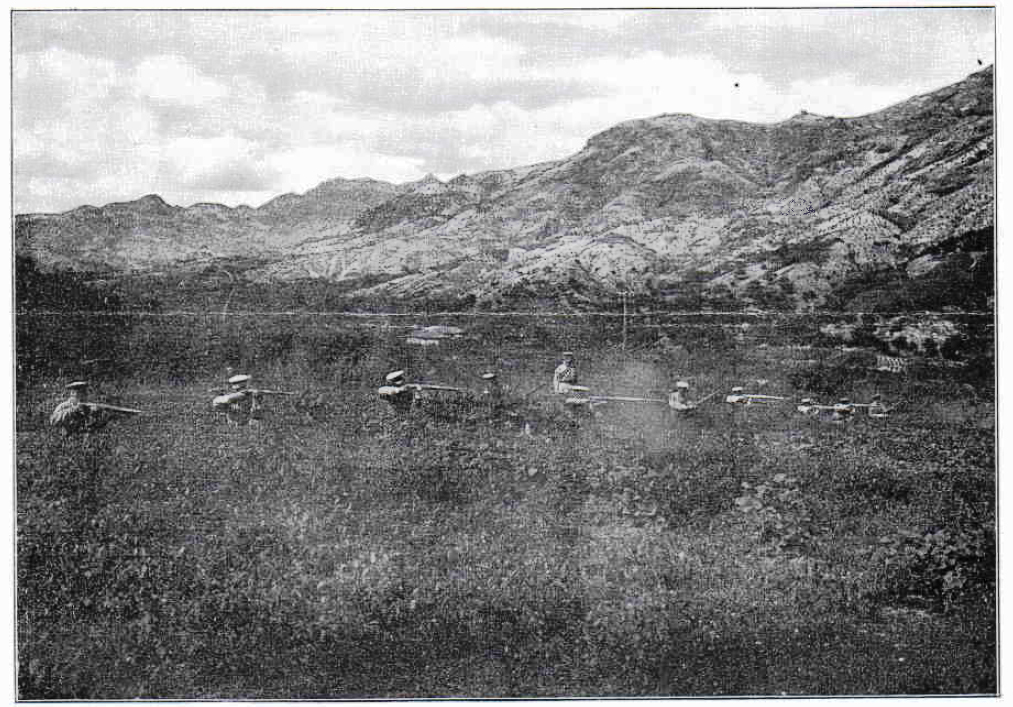

Drills by Korean assistant Military Police officers, 1912

Source: Gunjikeisatsu zasshi (Military Police Journal) 6-12, December 1912

The work of the Military Police was very wide-ranging and aside from conventional duties such as intelligence gathering and the Boto tobatsu (Subjugation of the Insurgents, the “war to maintain public order”). they were also responsible for things like the mediation of civil suits, border customs, guarding forests and graveyards, crackdowns (for example the suppression of workers), promoting the Japanese language, as well as instructing people how to go about their daily lives, for example in forest and agricultural improvement, promotion of side businesses, and tax obligations, etc. The administration of a person’s daily life expanded to the point that by April 1912, offences punishable by detention or fine included 87 ordinary activities. These included things such as “seditious public speaking”, “seditious writing”, “wild rumors”, “prayer”, “stone war” (a local folk custom), and “negligence in road cleaning”, all the way to being “vagrant and lacking an occupation”.

An address to the people by Military Police officers, 1915

Source: Gunji keisatsu zasshi (Military police journal) 9-6, June, 1915

According the December 1912 Hanzai sokketsu rei (Summary Regulations Regarding Crime) a head of a police station or Military Police officer need not put the accused through ordinary court proceedings, and could pass instant sentence with regard to crimes that entailed punishment of under three months imprisonment or a fine of under one hundred yen. The number of these instant sentences increased rapidly from approximately 18,100 in 1911 to around 82,100 in 1919. The Chosen chikei rei (Korean Caning Act) was applied only to Koreans and the number of canings was 5 times higher by 1916 than it had been in 1911. This shows that law and order measures were fast encroaching on people’s daily lives.

For instance, the fuzoku (public morals) police cracked down heavily on jumaki (roadside business establishments that sold food and drink and accommodated travelers for the night). The alleged purpose was not only to “protect the health of young Mainland (Japanese) men” (meaning: to prevent them from getting syphilis), but to crack down on the hiding places of thieves, in synchronization with a purge of society of large (Pyongbuk Military Police Warrant Officer Shinzo Kazunouchi, Shokuminchi to shūgyōfu torishimari ni tsuite [About the Colonies and Control of Prostitution] in Gunji keisatsu zasshi [Military police journal] Vol.10, No.4, April 1916). The military police believed half of Korean households to be operating hotels, with the owners giving shelter to independence movement activists. Therefore Koreans were under severe control. Here too we see how difficult it is to distinguish the “ordinary” and the “out-of the-ordinary” of everyday life. During investigations Korean assistant officers of the Military Police went in a variety of guises that included as hawkers, students, priests, monks, actors, drapers, stonemasons, used clothing merchants, beggars, steeplejacks, contractors, farmers, woodcutters, patients, chimney sweepers, candy sellers, and nuns.

Military Police disguise drill. Japanese soldiers are in front, Korean assistant officers in back. 1914

Source: Gunji keisatsu zasshi (Military Police Journal) 8-10, October, 1914

Japan had to change its colonial government after the March First Movement from “military rule” to “cultural rule”. And the normal police took over charge of maintaining public order from the military police. However, the basic view didn’t change that ordinary Koreans were like a riotous reserve army that required rigorous and preventative policing. After the March First Movement, because the lack of laws led the police to be unable to punish criminals, Ordinance No. 7 (“About Punishing Political Crimes”, April 15, 1919) was issued to cover an even broader area than had the Public Security Preservation Law. The part that differs from the earlier law is the following: in the new law, people who may also be punished are those who “interfere with peace and order by gathering in large groups with the aim of changing the government or causing disturbances” (Article 1). The fact that organized groups would be punished for preliminary conspiracy meant that they could apply it to overseas Koreans as well. There was a tripling in the police budget, as well as in the number of police officers and police stations. The number of weapons and military-style drills also increased. Furthermore, they strengthened their surveillance of people through a census. They organized the system to fight the “war to maintain public order” with the normal police force. So we can see the basis for the fact that despite Governor-General Makoto Saito’s claim of “cultural rule”, many Korean people still felt as if they were under military rule.

In the first stage of “the cultural rule”, even as restrictions were placed on freedom of speech, freedom of the press, and freedom of assembly, Korean newspaper and journals had started publishing and some groups were established. However, not only was censorship of both the press and assembly severe, arrests were also common. The Public Security Preservation Law, enacted on 12 May 1925 simultaneously in Japan and Korea, was first applied to the Communist Party of Korea. The late 1920’s saw nationalist and Socialist movements such as the June 10th Movement, the General Strike in Wonsan, the Gwangju Student Independence Movement, but these were suppressed heavily and the crack down was strengthened into the 1930s. The Chosen shiso han hogo kansatsu ho (Korean Protection and Surveillance Law for Thought Offense) was enacted in December 1936, in order to place on “probation” those whose sentence or indictment was suspended, as well as those released from jail, in an effort to promote a change in the direction of their thinking. Starting in the 1930s and continuing, the police system of leadership in society was further strengthened, and a deeper relationship developed with those in everyday governance. Things progressed at higher pace into the late 1930’s, and the Economic Police Department was established in order to gain access to and control over people’s financial lives.

Along the border between China and Korea, the military was suppressing nationalist movements as part of the “war to maintain public order”. After the March First Independence Movement, the Military Police were reinforced to crack down on independence movements such as the Righteous Armies of Jiandao, China. Unlike the Military Police in peaceful areas, the border Military Police were considered to have the same duties as they would in wartime, “because of rebellious Koreans” (Kobayashi in Hyesanjin, Kokkyo kenpei to futeisenjin [The Border Military Police and Rebellious Koreans], Gunjikeisatsu Zasshi [Military Police Journal], Vol.15 No.4, April 1921). Since then, the battlefields of the “war to maintain public order” had moved into Manchuria where the Northeast Anti-Japanese United Army was based.

Suppression by the police, the Military Police and the army essentially continued until August 15, 1945. Even so, there are those who claim that because of the “war to maintain public order” and crackdowns, there was in fact a free and modernized “ordinary” life to be lived under colonial rule. They can only do so by trivializing the most basic elements of the facts of what that rule was like.

<References>

Park Kyung sik, Nihon teikoku shugi no chosen shihai (Imperial Japan’s Domination of Korea). 2 volumes, Aoki-shoten, 1973.

Toshihiko Matsuda, Nihon no chosen shokuminchi shihai to keisatsu 1905-1945 (The Colonial Rule of Korea by Japan and its Police 1905 – 1945), Azekura-shobo, 2009.

Kan Tokusan, Kurikaesareta chosen no teiko to nippongun no danatsu gyakusatsu (Repeated Rebellion by Koreans and their Suppression and Massacre by the Japanese Army), Zen-ei (Vanguard), March 2010.

Shin Chang u, Chosen hanto no naisen to nihon no shokuminchi shihai (Internal War on the Korean Peninsula and Japan’s Colonial Rule) in Rekishi gaku kenkyu (Journal of Historical Studies) Vol. 885, October 2011.