Even in Pre-war Japan, the Licensed Prostitution System Was Criticized as “Slavery”

To refute an argument that “’Comfort women’ were not sex slaves but women licensed under the legalized prostitution system”, it was explained in an earlier section that “comfort women” weren’t “licensed prostitutes” and some women who worked as outside the legalised sex industry were also enlisted as “comfort women”. And it was explained that these women were equal to “sex slaves”. The military, or operators ordered by the military, enlisted them as “comfort women” through taking advantage of their circumstances as sex slaves. In other words, the custom of selling daughters into prostitution contributed to the large-scale enlistment of “comfort women”. When thinking about the “comfort women” issue, it is important to examine why such custom of selling their daughters into prostitution continued existing. Some people say that “it is true that the licensed prostitution system in Japan is inhumane from today’s point of view, but it was unavoidable since the custom was commonplace at that time”.

However, the argument that “the licensed prostitution system was commonplace in Japan” is completely wrong. This is because the licensed prostitution system and the custom of selling daughters into prostitution under the system wasn’t necessarily accepted in peacetime and many people who recognized it as “slavery” made efforts to abolish it, even in pre-war Japanese society. In other words, the licensed prostitution system wasn’t “commonplace” even in pre-war Japan.

What Is the Licensed Prostitution System?

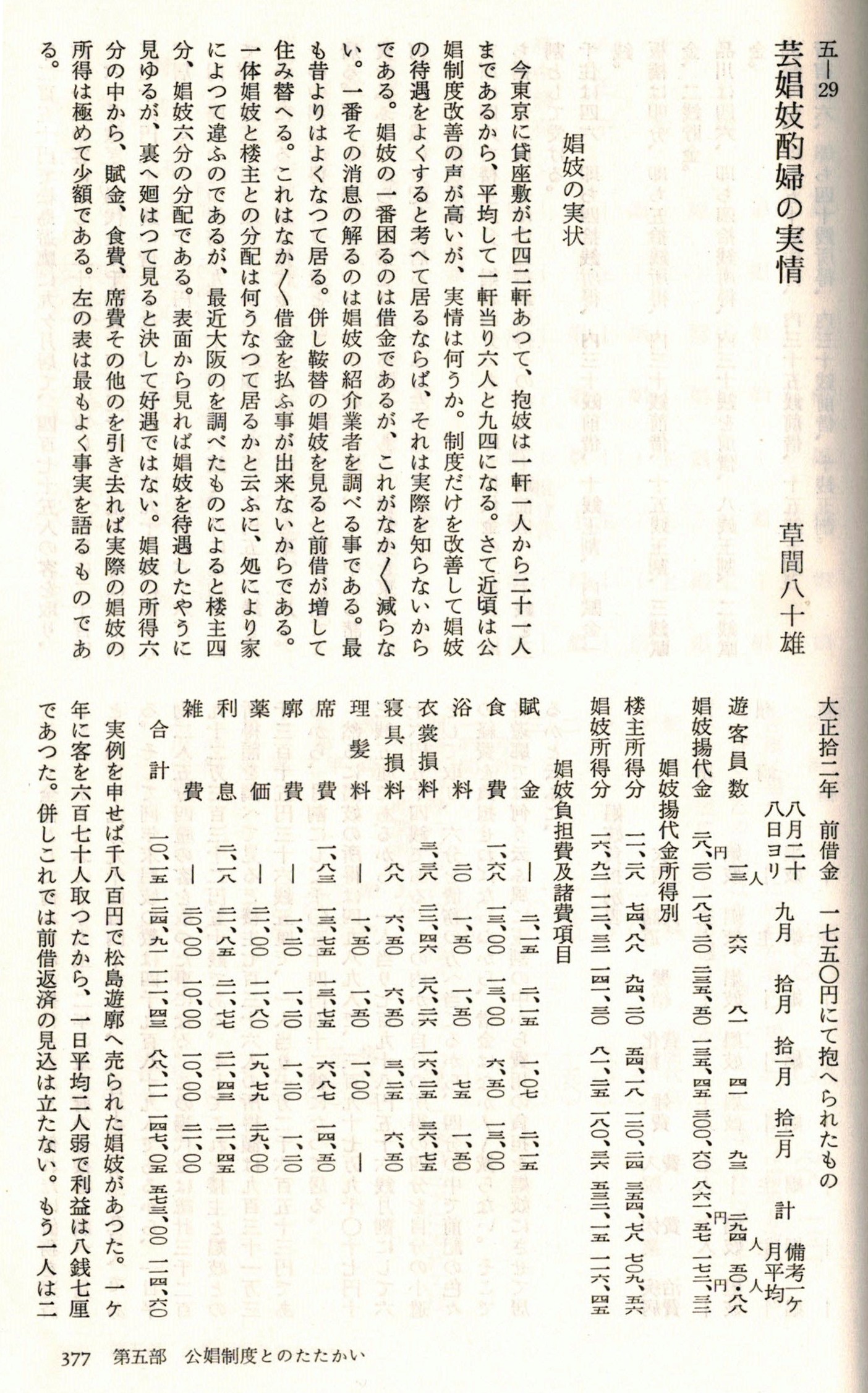

Under the licensed prostitution system, there was the custom of selling their daughters into prostitution which existed since pre-modern times. When they made a geisha or prostitution contract, parents were lent a large amount of money. And until the debt was paid off through working in the regulated sex industry, daughters hardly had any freedom of retirement. Moreover, a significant percentage of money customers paid for prostitution was collected by operators as revenue, and the debt was paid off from the remainder. So it took a long time to pay off the debt, and it often become impossible to pay it off because of exorbitant increases. Therefore, daughters were effectively sold by their parents. In Japanese society at that time, it was considered a virtue to devote oneself to parents or “families”. This moral framework was taken advantage of to justify the custom of selling daughters into prostitution and the women were forced to lead lives of prostitution without freedom of retirement.

Ordinance Liberating All Geisha and Prostitutes

Many people criticized this custom of selling daughters into prostitution from the mid nineteenth century . With the Maria Luz Incident as a turning point, an “Ordinance liberating all geisha and prostitutes” (Edict of the Grand Council of State, No. 295, Order of the Ministry of Justice, No. 22) was issued in 1872 declaring liberation of geisha and prostitutes. This incident arose when a Chinese person, who was about to be sold, escaped from the Peruvian ship “Maria Luz” harbored in Yokohama Port. A lawyer defending the Peruvian ship captain tried to make a plea in his favour on the grounds of hypocrisy to the governor of Kanagawa prefecture, Oe Taku, who took charge of this incident. He argued that Japanese geisha and prostitutes were forced to make contracts that appeared to be more slave-like than the one that was made with the escapee deck-hand. To avoid such criticism and maintain appearances as a civilized nation, Japan issued an edict liberating geisha and prostitutes who had been formerly equal in status to slaves (Edict of the Grand Council of State, No. 295). At this point, it was no longer acceptable in law during peacetime that geisha and prostitutes would be bound in debt and forced to work without freedom of retirement. Nevertheless, this practice wasn’t abolished in reality. After that, prefectural authorities evaded the law change through amending in regulation the name that was used for the prostitution venues in order to established them as sub-letting premises. In theory operators lent rooms to geisha and prostitutes committing prostitution by their “free will”, but in reality the traditional custom of selling daughters into prostitution continued.

Public campaigning for Free Retirement and Regulations for Prostitutes

However, the Movement for Abolition of the Licensed Prostitution System (Prostitution Abolition movement) occurred in the 1880s, and the movement continued after that without interruption. Japan Christian Woman’s Organization, which was established in 1886, criticized the custom of daughters being sacrificed for their “families” and the licensed prostitution system which allows men to commit sexual abandon and is against monogamy and consistently continued campaigning and changing shape into the Prostitution Abolition Movement after that. Under the influence of the Movement for Civil Rights and Freedom in the 1880s, the Prostitution Abolition Movement became brisk and propositions to abolish legalised prostitution were submitted to prefectural assemblies all over Japan. Especially, it was resolved in Gunma prefectural assembly to abolish the licensed prostitution system in 1889 and the system was abolished in 1893.

Being resistant to interference by sex industry operators, the Salvation Army expanded the Free Retirement campaign to help geisha and prostitutes wanting to retire. Some geisha, prostitutes and their support lawyers appealed to a court to demand retirement. In 1900, the Supreme Court passed a judgment stating that “a contract for the purpose of imprisoning women was null and void” and women could retire by their own free will even if they hadn’t paid off cash advances (this was referred to as “free retirement”).

Under this situation, “Regulations for prostitutes” was enacted in 1900 and freedom of retirement was stipulated there. In 1902, however, the Supreme Court passed judgment that a cash advance contract was separate from a geisha or prostitute contract. Under this interpretation, retired geisha and prostitutes were still obliged to pay off cash advances. Prostitution venue operators lent money to geisha and prostitutes’ parents for the purpose of imprisoning the women and making them work without freedom of retirement. It was obviously clear that a cash advance contract was integrated with a geisha and prostitutes’ contract. Therefore, to abolish human trafficking, a cash advance contract for the purpose of taking away freedom of retirement should have been criminalised. However, it remained legal. (Maki Hidemasa, “Human trafficking”, Iwanami Shinsho, 1971, Onozawa Akane, “Modern Japanese society and the licensed prostitution system―From the viewpoint of the history of people and international relations”, Kikkawa Koubunkan, 2010).

This was the main reason the custom of selling daughters into prostitution continued. Nevertheless, on the ground of “Ordinance liberating all geisha and prostitutes” and the Regulations for prostitutes, the Japanese government continued to make the false declaration after that that there was no trafficking of women in Japan.

The Prostitution Abolition Movement blossomed in the 20th century. When the Yoshiwara red-light district was completely destroyed by fire, a group called Kakuseikai was established in 1911 to oppose its reconstruction, and it played a leading role in the Prostitution Abolition Movement together with the Japan Christian Woman’s Organization. With the support of the Trafficking Abolition Movement in the Western countries, the “International Convention for the Suppression of the Traffic in Women and Children” was concluded in the League of Nations in 1921 (Japanese government ratified the convention, but reserving its application to Japan’s colonies and Article 5 on limitation of age to 21 years old. The latter reservation was withdrawn after that).

Onozawa Akane, “Modern Japanese society and the licensed prostitution system―From the viewpoint of the history of people and international relations”

It was prohibited under this convention to persuade women ①under the age of 21 to commit prostitution even if they consented and ②aged 21 and over to commit prostitution in fraudulent or forcible ways. Under the licensed prostitution system in Japan, women aged 18 and over were licensed to become prostitutes and they were forced to commit prostitution without freedom of retirement based on a cash advance contract regardless of age. So, the system clearly violated this convention.

Being boosted by such an international trend, the Prostitution Abolition Movement in Japan criticized the Japanese government’s false explanation that “Freedom of retirement was guaranteed for Japanese geisha and prostitutes and they committed prostitution by their own free will” and thereby strengthened the movement. Propositions to abolish the licensed prostitution system had been submitted many times to the Imperial Diet since 1920. Also, branch offices were organized to expand the Prostitution Abolition Movement to local areas and the education movement and movement to submit propositions to abolish the licensed prostitutes to each prefectural assembly was expanded widely. The Prostitution Abolition Movement was originally carried on by Christians, but abolition of the licensed prostitution system was pursued in the Women’s Movement including Women’s Suffrage Movement and Proletarian Movement, etc., at this time. Social Movements became active during Taisho Democracy after 1910s, and the infringement on human rights of prostitution under the licensed prostitution system was recognized as one of the most serious social problems.

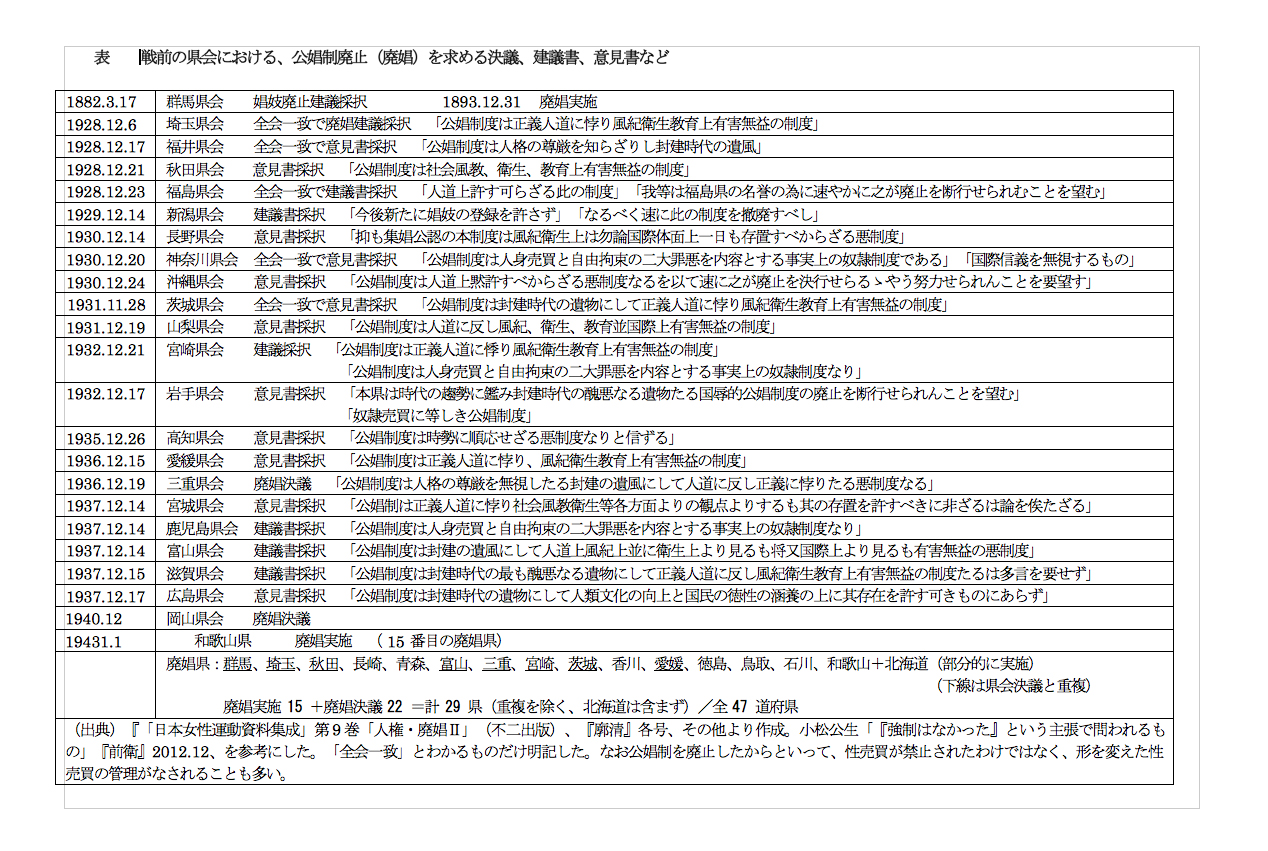

Consequently, as shown in the table below, it was resolved in many prefectural assemblies to abolish licensed prostitution. In 1934, the Home Ministry announced a policy to abolish the licensed prostitution system in the near future. Still, the licensed prostitution system wasn’t abolished in pre-war days.

List of prefectural assembly resolutions abolishing licensed prostitution in pre-war days

The Licensed Prostitution System in Japan Preserved by Japanese Government and the Court’s False Explanation and Sophism

For the above reasons, it is wrong to say that “the licensed prostitution system was commonplace in Japan” before the war. The system had already been criticized as “slavery” since the early modern times. And geisha and prostitutes’ personal liberty should have been protected based on provisions of free retirement in Ordinance liberating all geisha and prostitutes and Regulations for prostitutes. Nevertheless, the custom of selling daughters into prostitution continued and was connived by the courts and each prefecture’s sophism and connivance. The licensed prostitution system in modern Japan barely continued by Japanese government’s false explanation to international society that geigi, shogi and shakufu worked by their “own will”.