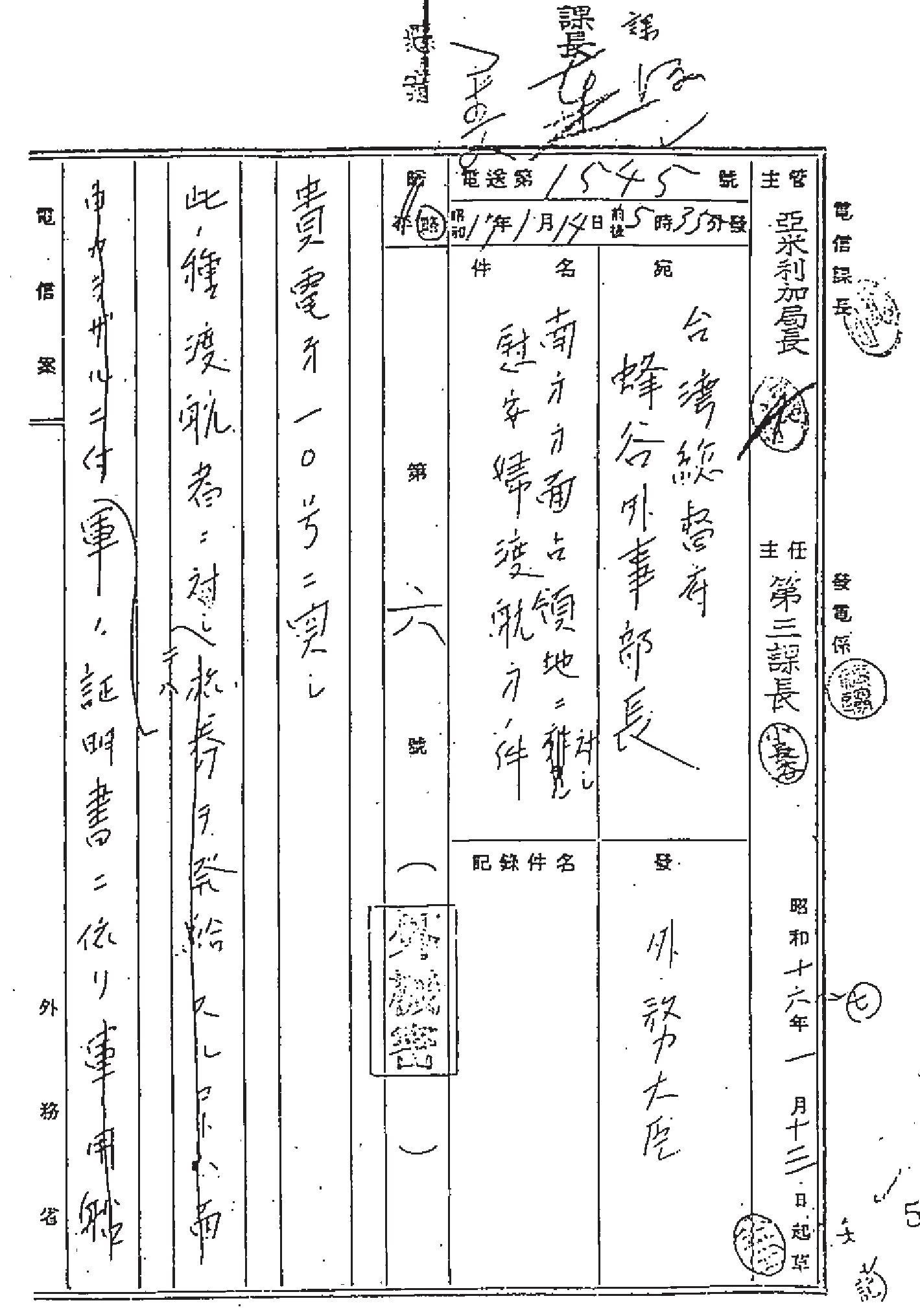

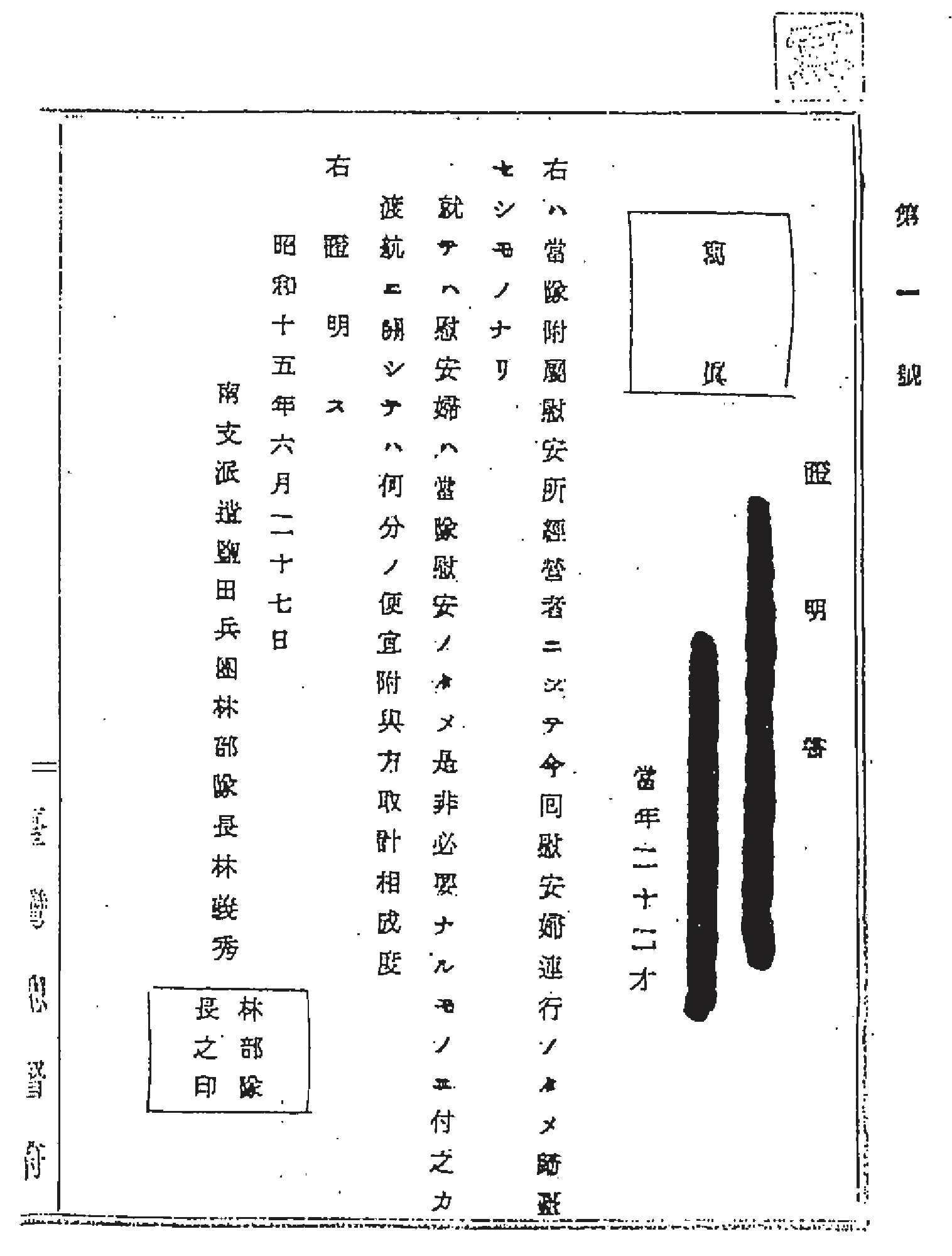

A Japanese Army and Ministry of Foreign Affairs document that shows the words “comfort women” and “comfort station” were used.

Among the reasons given when requesting the deletion of jugun ianfu (“military comfort women”) from school textbooks are that the term itself didn’t exist at the time, and that the designation “military” is unsuited since it implies the women were civilian employees of the military (Nobukatsu Fujioka, Monbu daijin e no kokai shokan [“An open letter to the education minister”]).

Is that really the case? Japanese military at the time initially had a variety of designations such as shakufu (“barmaids”) and ianjo jugyofu (“women employed at comfort stations”), but it was most common to call them ianfu (“comfort women”). And the places where these women lived were called ianjo (“comfort stations”) or gun-ianjo (“military comfort stations”).

The word jugun ianfu (“military comfort women”) was originally coined by Kako Senda in his work jugun ianfu (“Military Comfort Women”) (first published in Japanese in 1973), and has gained popularity since. They were taken everywhere the Japanese military went, so the word jugun (literal meaning is “following the military”) must have seemed like a perfect fit.

However since the 1990s, those involved in issues of wartime responsibility have criticized the term, saying that jugun (“military”) gives the impression the women followed the military voluntarily, and that the word “comfort” did not accurately reflect the reality that was faced by these women. They were victims of sex crimes, forced to conduct sexual activities, not “comforting” the soldiers. The claim was that the word “comfort” was deceptive and far removed from what actually occurred. So instead of “comfort women,” terms such as “sexual slave” and “military sex slave” have been used instead.

A document of the Japanese Army and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs that shows that the words “comfort women” and “comfort station” were used.

On the other hand, there is the opinion that, even though the term does not accurately reflect the situation, it is a historical fact that it was used, and that it is important to keep historical record of the fact that the Japanese army used such a deceptive expression. It has become popular in these cases to avoided using only jugun (“military”) and make the subject clearer, calling them “Japanese Military comfort women”.

Nor is using the word jugun (“military”) a mistake. A quick reading-up of history will tell you that the term does not mean they were civilian employees of the military. Also, as seen in terms such as “military nurse”, “military journalist” and “military authors,” there are other instances of forced enlistment which invalidates the opinion that the word connotes the meaning of “voluntary”. In essence, the designation jugun ianfu (“military comfort women”) accurately describes the situation these women were in, in the sense that they were ordered to follow where the military went (this is a point on which many opinions differ).

If we argue that we cannot use words that were not in use at the time, we cannot write history. It need not be said that most terms describing historical events were not used at the time, but were invented after the fact.

It is utterly laughable to argue that since the term “military comfort women” was not used at the time, there were no such persons, or that it should not be included in school textbooks.