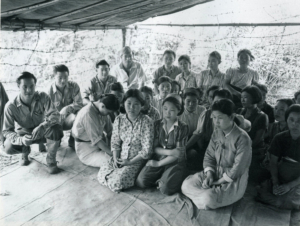

A researcher who listened to the testimonies of many Korean former “comfort women” points out, “The damage suffered by ‘comfort women’ did not end at the comfort stations, but began there.” (Yang Hyun-ah) This is also true of Chinese, Filipina, Dutch, and other former “comfort women” and victims of sexual violence from various Asian countries and communities.

A researcher who listened to the testimonies of many Korean former “comfort women” points out, “The damage suffered by ‘comfort women’ did not end at the comfort stations, but began there.” (Yang Hyun-ah) This is also true of Chinese, Filipina, Dutch, and other former “comfort women” and victims of sexual violence from various Asian countries and communities.

While how the women were treated after the war (please refer to item https://fightforjustice.info/?p=9584 in the Primer/ Introduction) differed depending on their ethnic groups, their postwar lives are quite similar irrespective of ethnic differences. Even today it is difficult for victims of sexual violence to claim damages, but former “comfort women” lived at a time when women faced incomparably greater pressure to “stay virtuous” and “retain sexual purity” and led lives full of hardship without being able to make complaints about the harm they suffered from sexual violence after the war. Still, it is not as if they all lived the same life. Let’s take a look at their lives after the war in terms of trauma and PTSD.

High Rates of PTSD Among Victims of Sexual Violence

You may be familiar with the concepts of trauma and PTSD. Trauma means “psychological or emotional harm resulting from a person’s exposure to devastating events” such as life-threatening experiences or sexual assault. Traumatic experiences are so impactful that “it is hard to describe them in words” and “they are beyond description.” One of the responses to trauma is PTSD (post- traumatic stress disorder). Symptoms of PTSD may include, for example, ongoing, prolonged, and repeated alterness or hypervigilance, sudden recall of memories in flashbacks or nightmares, avoidance of anything reminiscent of traumatic experiences, an absence of emotional reactions, and survival guilt.

There are gender (a socially constructed category) differences in traumatic experiences in that while men may develop PTSD from disasters, accidents, violence, combat, being threatened with weapons, and the like, an overwhelming proportion of women develop PTSD from the damage of sexual violence. Furthermore, it is said that rates of PTSD stemming from the harm of sexual violence are higher than those of other traumatic experiences (according to Miyaji Naoko). “Comfort women” and victims of sexual violence during war are diagnosed with PTSD or Complex PTSD. Let’s look at some cases of victims of sexual violence who were Korean or Chinese former “comfort women.”

PTSD and Alienation from Family and Society: the Case of Korean Women

Many Korean victims developed chronic PTSD, and the basis of their diagnoses is as follows. (According to Yang Hyun-ah, eleven out of fourteen victims in Incheon Sarang Hospital, South Korea, in 2000 had developed PTSD.)

1) When they were “comfort women” they felt the threat of death and experienced a sense of helplessness and fear as they or their peers were beaten by soldiers with bayonets, etc.

2) In their later lives, they felt fear and avoided men, especially soldiers.

3) They made efforts not to think of their earlier traumatic experiences and avoided forming relationships with men, falling in love, marriage, etc. to avoid having to recall those times.

4) They frequently have difficulty sleeping.

5) These symptoms have persisted for decades, and the women often think of committing suicide.

According to the research findings of the Korean Council for the Women Drafted for Military Sexual Slavery by Japan, out of 192 self-identified “comfort women” victims, almost all of them suffered from serious problems such as social anxiety disorder, emotional instability, hwabyeong (a syndrome brought on by the suppression of anger within one’s body), feelings of shame and guilt, anger and resentment, self-contempt, hopelessness, melancholy, or a sense of isolation.

The after-effects of the harm they suffered are not only psychological, but physical too. The abuse and violence inflicted by traffickers or soldiers with a bayonet led to some victims losing their sense of hearing or sight, and the scars of sword cuts remain as daily reminders of trauma.

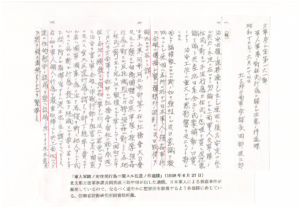

抵抗したために軍刀できられた朴永心さんの首筋の傷跡。

Also, they have suffered from irreparable harm to their genitals and reproductive organs resulting from prolonged and repeated rape. Those infected with sexually transmitted diseases (such as syphilis) at comfort stations were not given treatment or care even after the war and went on to suffer ongoing genital or uterine complications. Because some soldiers refused to use a condom, some women became pregnant against their will and underwent forced abortion procedures; there were many examples of both still and live births. Many women were made infertile or did not want to get married. After the war, in a patriarchal society where “it is a matter of course to get married” and “it is women’s duty to have a baby,” they had trouble living as women. In some cases, sexually transmitted diseases were passed on to the next generation, affecting children’s physical or mental health.

After-effects have lingered at the social level too. Women who had internalized the values of a patriarchal society that requires women to “keep their virtue” and “retain sexual purity” kept silent even after the war to hide their traumatic past from their families and communities. They led disrupted and unstable lives in that they could not return to their hometowns due to feelings of shame, it was hard for them to get married (or they refused to do so), they could not have a baby even after getting married to or living together with men, they were driven away by rumors that they were former “comfort women” or they were reduced to poverty. Some women attempted suicide. These long-term symptoms were exacerbated by the Japanese government’s refusal to admit the fact that unlawful acts were committed or pay compensation.

PTSD and Isolation on “a Bed of Thorns”: Chinese Victims

How about victims in occupied areas such as Chinese? For example, unlike Japanese or people from colonies, victimized women in Shanxi province, China, suffered damages in local areas they had lived in. Because victims’ families, relatives or familiar villagers knew that they suffered damages from sexual violence, they were sitting on “a bed of thorns” (hard places or circumstances) and couldn’t make public appeals about their damages.

Ms. Wan Ai Hua was abducted by the Japanese military, repeatedly raped and suffered bone injury, grew short and had a hearing loss in right ear by torture. After the war, she moved to another place to avoid her acquaintances’ eyes. A couple got married with knowing the fact of damages and got along well, but even the husband was persecuted, and the woman committed a suicide as a women’s disease caused by damages from Japanese soldiers got worse.

Ms. Wan Ai Hua was abducted by the Japanese military, repeatedly raped and suffered bone injury, grew short and had a hearing loss in right ear by torture. After the war, she moved to another place to avoid her acquaintances’ eyes. A couple got married with knowing the fact of damages and got along well, but even the husband was persecuted, and the woman committed a suicide as a women’s disease caused by damages from Japanese soldiers got worse.

A psychiatrist, who examined 6 Chinese victims, diagnosed that the peculiar symptoms of PTSD (memory fragmentation) were shown; although victimized women vividly recalled memories of each one of the damages (traumatic memories), they didn’t clearly understand the context. Also, it is made clear that it can be regarded as child abuse because many women suffered damages in their teens, “PTSD exists more than 50 years after the war” and they suffered from “anxiety” and “melancholy” (depression) (According to Kuwayama Norihiko).

Like this, because of the Japanese military “comfort women” system, damages from sexual violence beginning with the systematic rapes, mental and physical prognostic symptoms continuing after the war and social stigma, being unable to make appeals about their pasts and damages, they had to spend a long time in isolation and silence until movement in resolving the “comfort women” issue (→Introduction 9) began in the 1990s.

However, Yang Hyun-ah, who examined victims’ lives after the war, noted that victimized “comfort women” should not be regarded as “miserable and helpless victims” and giving testimonies requires enormous courage and leads to cure for their diseases. Moreover, she classified damages suffered by “comfort women” into 3 categories; damages with “complexity” having mental, physical and social aspects, damages with “continuity” that pains continue as justice isn’t established in the “comfort women” issue and damages with “contemporary” that pains are reproduced in a relationship with contemporary society such as indifference to and ignorance and distortion of damages.

What is most important to restore the honor of the victims should be, imagining if “we, our sisters, lovers or friends were suffered damages (victims)”, to become interested in and have compassion on their damages and pains.

〈References〉

・Edited by Women’s Active Museum on War and Peace, “Testimonies Memories for the Future Collection Ⅰ of Testimonies of Asian ‘Comfort Women’”, Akashi Shoten, 2006.

・Ibid. “Testimonies Memories for the Future Collection Ⅱ of Testimonies of Asian ‘Comfort Women’”, Akashi Shoten, 2010.

・Yang Hyun-ah, “Damages Suffered by Korean Who Were ‘Comfort Women’ of the Japanese Military Continuing after Colonial Rule”, ibid. “Testimonies Memories for the Future Collection Ⅱ of Testimonies of Asian ‘Comfort Women’”, 2010.

・Korean Council for the Women Drafted for Military Sexual Slavery by Japan, “Statistical Materials of Testimonies of the Japanese Military ‘Comfort Women’(Korean character)”, 2011.

・Edited by Ishida Yoneko and Uchida Tomoyuki, “Sexual Violence in Ocher Village―War Never Ends to ‘Daniang’”, Sodosha, 2004.

・Women’s Active Museum on War and Peace (wam), “One Day the Japanese Military Came―Rapes and Comfort Stations in the Battlefields in China (wam catalog 6)”, 2008.

・Kuwayama Norihiko, “Trauma and PTSD Suffered by Former Chinese ‘Comfort Women’”, “Quarterly Journal Study on War Responsibility“, No. 19. 1998.

・Judith L. Herman (translated by Nakai Hisao), “Trauma and Recovery”, Misuzushobo, enlarged edition, 1999.

・Miyaji Naoko, “Trauma”, Iwanamishinsho, 2013.