There were differences in how the women were treated after the war depending on the ethnic groups they belonged to and the places where they were taken. Women already living in occupied areas such as Chinese and Filipinas suffered from sexual violence as “comfort women” mainly in their local or home areas, while Japanese women and women from colonies such as Korea and Taiwan were transported from their homelands to distant occupied areas and battlefields where they were forced to become “comfort women.” They were taken to a variety of areas ranging from China and Asian Pacific Islands that had been invaded and occupied by the Japanese military to dangerous front lines. Some Chinese and Indonesian women were also transported overseas.

Japanese “comfort women” who were in occupied areas or other locales at the time of Japan’s defeat returned to Japan via repatriation ships along with Japanese settlers and others. (Nagasawa Kenichi, “Hankou Comfort Station” etc.) Nevertheless, their postwar experiences were filled with hardship. (Refer to “Testimonies: Japanese ‘Comfort Women’”)

Korean and Taiwanese “Comfort Women” Left Behind

What happened to women from the colonies? Korean women were not informed of Japan’s defeat and were left behind in local areas by the Japanese military. There were three types of cases: 1) those left behind in battlefields who died, 2) those who returned home by themselves, and 3) those who remained in local areas against their will.

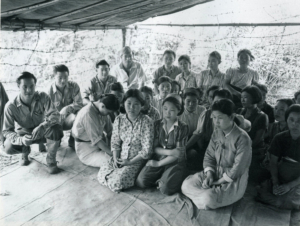

1) First, in the cases of those left behind in battlefields who died, it seems that many women were left behind in enemy camps as the Japanese military escaped. They could not understand where they were, did not know local languages, did not have valid currency, and were thus left in a dangerous situation where they died without finding a way to return to their home country. What happened to them? This photograph shows the dead bodies of Korean “comfort women,” and according to records, “Trenches were full of dead bodies of women. Almost all of them were Korean.” (The photo shows the border between Tengyue, China and Burma in 1944.) Moreover, during the deteriorating war situation from late 1944 to the spring of 1945, each unit on the Philippine front left behind Korean “comfort women” who had accompanied the unit “like garbage.” (Senda Kako, Military Comfort Women) Similar things seem to have happened in various places after Japan’s defeat.

中国の騰越(ビルマ国境地帯)の朝鮮人「慰安婦」の遺体(1944年9月)。

2) With regard to the cases of those who returned home by themselves, Ms. Huang Jin Zhou returned home from China by herself, and Ms. Kang Duk-kyung (pregnant by a Japanese soldier) did so from Japan. Ms. Park Du-ri returned to her country with a Korean man who ran errands at a comfort station in Taiwan. Ms. Park Yong-sim was detained in Kunming prisoners’ camp and came back to South Korea from Chongqing with the Korean Liberation Army. It took four years for Ms. Choi Kap-son, who was taken to China, to make it back to Korea on foot, selling tofu along the way. We can understand how dangerous, difficult and miraculous it was that they were able to return back to their countries. However, even after returning their lives were filled with hardship and suffering. (Please refer to item #7 in the Introduction/Primer).

3) There were also many cases of those who remained where they had been taken against their will, such as is evident in the case of Wuhan in inland China. It is said that the largest Japanese military comfort facility in China was established in Jiqingli, Wuhan in November 1938, and 130 Japanese women and 150 Korean women were forced to become “comfort women” at about 20 comfort stations there. (Yamada Seikichi, “Logistics in Wuhan”) According to Captain Nagasawa Kenichi, a medical officer, former Japanese “comfort women” returned to Japan on repatriation ships in the spring after Japan’s defeat according to their home prefecture. (Nagasawa, Hankou comfort station) He asserts that former Korean “comfort women” seemed to return to their homelands with the Korean Liberation Army, but that was not necessarily true.

Ms. Song Shin-do, who was forced to become a “comfort woman” in Wuhan, went to Japan at the behest of a former Japanese sergeant who abandoned her there. Women such as Ms. Ha Sang-suk, hesitated initially when a chance to return presented itself because of “feelings of shame” and ended up remaining near Wuhan against their wishes. According to Ms. Ha, the number of them was 32 in the late 1950s and 9 in the 1990s. (Korean ‘Comfort Women’ Taken to China)

Moreover, quite a few Korean women had to remain in the areas where they had been taken. Ms. Park Ok-seon, Lee Ok-seon and Kim Sun-ok were taken to Northeast China (so-called “Manchuria”), Ms. Noh Su-bok was taken to Singapore and remained thereafter in Thailand, and Ms. Bae Bong-gi was taken to Tokashiki Island, Okinawa. (Korean ‘comfort women’ left behind) Only after half a century had passed in the 1990s and 2000s were they able to return with the help of the South Korean Government, support organizations, etc. It was the same for Taiwanese women.

It is because these victimized women, who are rightly called “survivors,” were able to return to their countries or survive in local areas and live through great hardships that we can hear their testimonies.

As described above, the Japanese military repatriated Japanese “comfort women,” but it did not take measures to return former Korean or Taiwanese “comfort women” taken from colonies to battlefields or occupied areas under the “comfort women” system the military designed and implemented. The Japanese military and government’s abandonment of postwar and colonial responsibility began with the abandonment of “comfort women” who were left behind as soon as the war ended.

Left Behind from Postwar Compensation

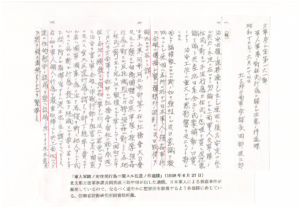

The Japanese government neglected and ignored this issue for more than half a century until Korean and other Asian victims began testifying one after another in the 1990s. The Japanese government officially admitted the military’s involvement after Ms. Kim Hak-sun came forward under her real name and began to testify for the first time in South Korea on August 14, 1991, and it was reported that there were materials showing the military’s deep involvement in the Library of the National Institute for Defense Studies in January 1992. Still, the Japanese Government did not take measures to repatriate former “comfort women” survivors who had been unable to return home.

What about postwar compensation? “In the spirit of national compensation,” the Japanese government paid individual compensation (military pension) to former Japanese male soldiers and civilian employees beginning in 1952. In contrast, “comfort women” have not received individual compensation or reparations from the Japanese government. In 1995, the Japanese government established the “National Fund for Peace in Asia for Women” (National Fund or Asian Women’s Fund), but the purpose of this fund was not to provide national compensation but “atonement money” donated by civilians. The differential treatment of Japanese soldiers and civilian employees in comparison with former “comfort women,” who were left behind without postwar compensation, is clear.

<Citations, References/Video>

・Senda Kako, Military Comfort Women, Sanichi Shobo, 1978.

・Yang Hyun-ah, “Damages Suffered by Koreans who were ‘Comfort Women’ of the Japanese Military Continuing after Colonial Rule” in Testimonies: Memories for the Future, a Collection of Testimonies of Asian ‘Comfort Women,’ Akashi Shoten, 2010.

・Yamada Seikichi, Logistics in Wuhan, Tosho Shuppansha, 1978.

・Nagasawa kenichi, Hankou Comfort Station, Tosho Shuppansha, 1983.

・The Korean Council for the Women Drafted for Military Sexual Slavery by Japan and Korean Research Institute for Chongshindae, eds., and translated by Yamaguchi Akiko, Korean ‘Comfort Women’ Taken to China, Akashi Shoten, 1996.

・Catalog published by the Women’s Active Museum on War and Peace, Korean ‘Comfort Women’ Left Behind, 2006.

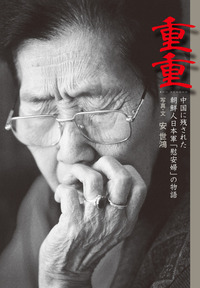

・Written and photographed by Ahn Se-hong, Layer by Layer―Stories of Korean Women Left Behind in China Who Were ‘Comfort Women’ of the Japanese Military, Otsuki Shoten, 2013

・Byun Young-joo, director, House of Sharing [Part of the Habitual Sadness/Najun Moksori Trilogy], 1995.